|

American History |

|

Subscriber Exclusive | The Epoch Times |

|

|

“The Custer Fight” by Charles Marion Russell. Library of Congress. This battle was part of the Sioux Nation’s response to the United States’s breaking the second Treaty of Fort Laramie. (Public Domain) |

|

The second Fort Laramie Treaty proclaimed that the fight against the Sioux Nation would “forever cease,” much like the first Fort Laramie Treaty had promised a “lasting peace.” Neither of the treaties’ promises lasted long, especially after gold was found on the Sioux’s sacred land—the Black Hills. The fight for the Black Hills saw the rise of the Lakota war chief, Crazy Horse, and some of the most important and consequential battles of the Indian Wars. |

|

|

Treaties, Gold, and the Last Battle of Crazy Horse |

|

In ‘This Week in History,’ peace between the United States and Sioux Nation ended with the Black Hills Gold Rush, leading to the Great Sioux War. |

|

|

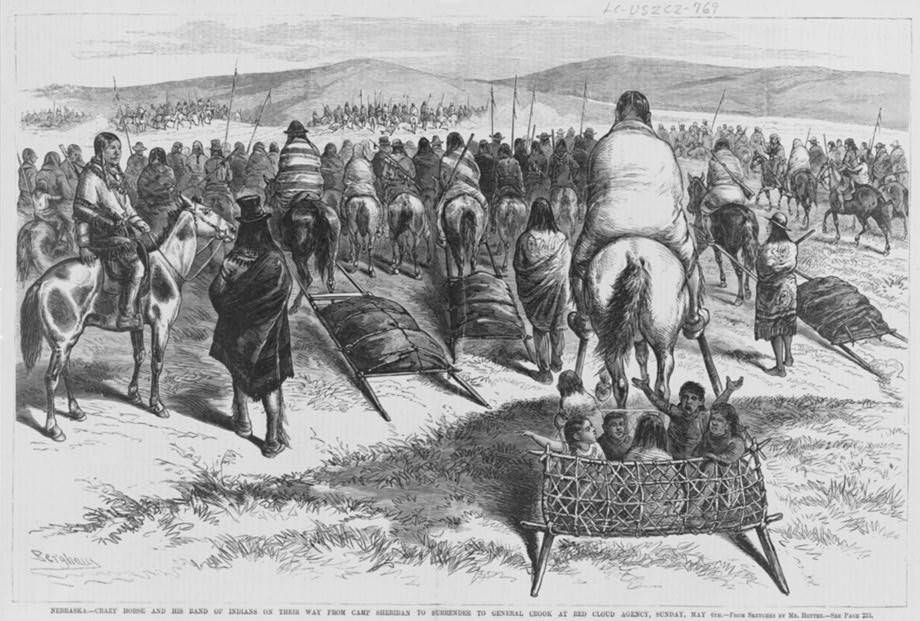

Crazy Horse and his band of Oglala on their way from Camp Sheridan to surrender to Gen. Crook at Red Cloud agency, on Sunday, May 6, 1877. (Public Domain) |

|

By Dustin Bass |

|

On Sept. 17, 1851, 21 leaders, representing the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, and Assiniboine, and representatives of the U.S. government, signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The treaty was designed to secure safe passage for settlers moving west through Native American lands and assign boundaries for each nation’s “respective territories.” By 1854, the “effective and lasting peace” formulated by the treaty had devolved into the Plains War.

After years of intermittent fighting, a peace conference, held in 1867 at Medicine Lodge, Kansas, led to the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, and Cheyenne agreeing to relocate to western Oklahoma. A year later, another peace conference was held at Fort Laramie.

“From this day forward all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease.” This was the opening line of the second Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed on April 29, 1868, between the U.S. government and the Sioux Nation, which included the tribes of the Blackfeet, Brulé, Cuthead, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Oglala, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, Santee, and Yanktonai. The agreement established the Great Sioux Reservation in today’s South Dakota, part of which encompassed the Sioux’s sacred Black Hills.

“The Government of the United States desires peace, and its honor is hereby pledged to keep it,” the treaty stated. “The Indians desire peace, and they now pledge their honor to maintain it.”

The treaty required the tribes relinquish thousands of acres of land, while retaining their hunting and fishing rights to those lands. But the Black Hills belonged to them.

Rumors, however, began to spread about the Black Hills. The rumors were not about treaty violations. The rumors were about gold.

The Black Hills ExpeditionIn 1874, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman authorized Lt. Col. George Custer to conduct an expedition into the Black Hills to scout areas to build forts for the U.S. Army. That was the official reason for the Black Hills Expedition. The unofficial reason was to discover whether or not the gold rumors were true. On July 2, Custer, joined by approximately 1,000 men, most of whom were soldiers, set out from Fort Lincoln, nestled along the west side of the Missouri River, to scout the Black Hills.

The expedition was a massive undertaking, which included 660 mules, 700 horses, herds of cattle, and more than 100 wagons. There were engineers, scientists, musicians, reporters, a photographer, and, most consequentially, two miners.

A month into the expedition, the two miners, Horatio Ross and William McKay, discovered gold flakes at French Creek. Upon the expedition’s return to Fort Lincoln, Custer reported that “examinations at numerous points confirm and strengthen the fact of the existence of gold in the Black Hills.” Immediately, the Black Hills Gold Rush began, and thousands of miners and prospectors flooded Sioux territory.

Despite the lofty promise that war between the United States and the Sioux Nation would “forever cease,” forever proved rather brief. From the signing of the treaty in 1868 to the Expedition in 1874, that is, within six years, peace had disintegrated and war had come.

The Rise of Crazy HorseTasunke Witko was a member of the Oglala band of the Lakota, part of the Sioux Nation. He was born sometime around 1840 (though Sioux author and physician, Charles Eastman, suggests 1845). His name was not always Tasunke Witko, or more famously, Crazy Horse. He was first the son of Crazy Horse, and his first name was Curly Hair. As he grew up, he also earned the name His Horse Looking.

He proved his bravery as a young warrior. A life-altering moment took place when he witnessed the Grattan Massacre (or Grattan Fight) in 1854, an avoidable dispute that resulted in the death of Brevet 2nd Lt. John Lawrence Grattan, 29 soldiers, and Conquering Bear, chief of the Brulé Lakota. Conquering Bear had been the reluctant representative during the first Fort Laramie Treaty signing.

The Grattan Massacre launched the First Sioux War between the Lakota tribes and the U.S. Army.

It was also during the year 1854 that Crazy Horse ventured on a vision quest, an ancient tradition where one seeks guidance from a divine manifestation. Fasting from food and water for several days, Crazy Horse witnessed a vision of a warrior on horseback. The warrior’s hair was unbraided and he had a stone behind one ear. His horse was wild and the people in the vision tried to restrain it, but failed. A storm engulfed the people and the warrior became part of the storm with a lightning streak on his face and hailstones on his body. In the vision, the rider was impervious to bullets and arrows.

In every battle after the vision, Crazy Horse painted a lightning bolt on his face and hailstones on his body. He never tied his horse’s tail and only wore a single feather. He also believed the vision indicated he would not die in battle, a belief that proved accurate.

After a battle against the Arapaho in 1858, the Oglala warrior was given the name Crazy Horse. His father took the name Worm. Over the years, Crazy Horse rose to prominence among his tribe and among the Sioux Nation. He became a “shirt wearer” in 1865, which was a person who counseled on matters of tribal welfare, hunting, campsites, and war.

The Black Hills CouncilHe played important roles in numerous conflicts against the U.S. Army, including the Battle of Platte River Bridge, Red Cloud’s War, and the Battle of the Rosebud. After Red Cloud’s War ended in 1868, Chief Red Cloud, of the Oglala, signed the second Fort Laramie Treaty, choosing to move to the reservation. Crazy Horse subsequently became the Oglala war chief (this is not the tribal chief). Red Cloud’s area of the reservation in Nebraska became the Red Cloud Agency.

Crazy Horse, as well as Sitting Bull, another warrior leader of the Lakota, refused the reservation life, choosing to continue the fight against the Americans. After Custer’s expedition in 1874, and the influx of miners throughout the following year, the problems intensified. Gold fever had possessed the American population and the Native American tribes fought to keep soldiers and miners out of the Black Hills, with some degree of success. In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant approved the commissioner of Indian Affairs to coordinate a conference “to treat with the Sioux for the Relinquishment of the Black Hills.”

Throughout the summer, commissioners traveled between the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies to select a location for the Black Hills Council, which would also be called the Grand Council. The Red Cloud Agency was selected with Sen. William B. Allison of Iowa chairing the meeting. During the month of September, the council took place, though many Sioux leaders refused to attend, among them Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull.

For reasons on both sides, the Black Hills Council ended in failure. The commissioners had been given permission to purchase the Black Hills for as much as $6 million. It appears there may have been the possibility of sale for $7 million. The council’s time restrictions, further hampered by poor interpretations during discussions, resulted in a rushed conference, at a moment when time was of the utmost importance.

While Red Cloud and Spotted Tail and their respective people returned to their reservations, many of the Lakota did not, choosing rather to hunt and roam the plains, and fight against the rising tide of settlers, prospectors, and mining companies. Hostilities continued, and the decision of the Grant Administration to issue an ultimatum only intensified hostilities.

The Boiling PointOn Dec. 3, the administration demanded all Lakota report to a reservation by Jan. 31, 1876, or face the U.S. military. The combination of increased incursions into Sioux lands and resistance to the ultimatum led directly to the Great Sioux War, also known as the Black Hills War, where the Lakota allied with the Northern Cheyenne.

The year 1876 was a banner year militarily for the Lakota, but it also spelled the end of the resistance, as well as the end of Crazy Horse. It was also a banner year for the Black Hills Gold Rush.

On April 9, Hank Harney, and brothers Fred and Moses Manuel discovered one the largest gold veins in American history. The miners laid claim to the area and named it Homestake Mine. The mine, which reached depths of 8,000 feet, would produce approximately 40 million ounces of gold over the span of 126 years. As word spread of this discovery, miners and prospectors flooded the area, now with the U.S. government’s blessing.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army, led by generals George Crook, Alfred Terry, and John Gibbon, looked to pin in the Native American alliance and bring an end to the war.

The Last Stands

In June, word spread throughout the Wolf Mountains of southern Montana that the Army was nearing. The armies of Crook, Terry, and Gibbon were planning to meet. On the morning of June 17, however, along Rosebud Creek just east of the Big Horn, Crazy Horse led approximately 1,500 warriors in an attack on the unprepared American Army. Thanks to Crook’s Crow and Shoshone warriors and scouts, they were alerted just in time and were able to survive the Sioux attack and withdraw. The Battle of the Rosebud was considered a draw.

A week later, as the Army of Gen. Terry advanced near Big Horn, Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull led an attack against Terry’s subordinate officer: Lt. Col. George Custer. On June 25 and June 26, the Battle of the Little Big Horn, famously known as Custer’s Last Stand, took place, leading to the rout and destruction of Custer’s 7th Cavalry.

The result of this battle led Congress to double its efforts to end the wars. The U.S. Army began a campaign of constant pursuit and attack, driving Crazy Horse and his warriors into the Wolf Mountains. In October, Col. Nelson Miles captured approximately 2,000 warriors, forcing them to report to their reservations. Miles continued his campaign to pursue Crazy Horse.

The winter of 1876 to 1877 was harsh, but Miles didn’t allow the weather to decide the outcome. His troops and the Crazy Horse-led Lakota fought numerous skirmishes in the first week of 1877 in the Wolf Mountains. But it was during this week in history, on Jan. 8, 1877, that Crazy Horse conducted his last stand.

The Battle of Wolf Mountain, a five-hour battle, ultimately spelled the end of Crazy Horse’s campaign. Facing immense odds and dwindling resources, along with numerous allies opting for the reservation, Crazy Horse was finally convinced through various intermediaries, including Spotted Tail, to surrender. He, along with his Lakota warriors, as well as those of their Cheyenne allies, surrendered at Fort Robinson in Nebraska on May 6. |

‘Could anyone expect less?’After the Great Sioux War ended, Crazy Horse took his people to Red Cloud Agency, while Sitting Bull led his people into Canada. Perhaps due to a mistranslation or simply due to fear of Crazy Horse’s powerful influence, he was arrested on suspicion that he was planning a rebellion. During a scuffle to place him behind bars, he was tragically bayoneted on Sept. 5, 1877. Years later, Sitting Bull was killed on Dec. 15, 1890, during a relatively similar event when he was arrested on suspicion that he was involved with the rebellious Ghost Dance movement.

Regarding Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, Red Cloud continued his efforts to improve his people’s conditions and fight for land rights. He converted to Christianity, changed his name to John, and died in 1909 of natural causes. Spotted Tail, however, died at the hand of his political rival, Crow Dog, in 1881.

Reflecting on the wars against Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and the Sioux Lakota tribes, Gen. Philip Sheridan stated,

“We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them, and it was for this and against this that they made war. Could anyone expect less?” |