A ‘clean slate’ for Kentuckians convicted of nonviolent or low-level crimes?

By McKenna Horsley,

John Bowman made mistakes, but he wants to move forward with his life, he told Kentucky lawmakers last week.

The Louisa man has been in recovery for five years after overcoming an active addiction of 24 years. His drug-related felonies continue to affect him and his family today.

He highlighted some challenges he and other formerly incarcerated people face while reentering society — when seeking employment, for example, or trying to volunteer at their kids’ schools.

“Kentuckians like me across the commonwealth have turned their lives around and are productive members of society again,” Bowman said, adding that a Clean Slate law could have economic benefits by making more people able to rejoin the state’s workforce.

He was one of a few advocates from Dream.org s peaking in favor of adopting an automatic expungement law in Kentucky at a July 20 meeting of the Interim Joint Committee on Judiciary.

Kimberly Poore Moser (LRC Public Information)

They, along with Rep. Kimberly Poore Moser, R-Taylor Mill, are calling on the General Assembly to give low-level and nonviolent offenders a clean slate.

However, two of her colleagues, Sen. John Schickel, R-Union, and Rep. Stephanie Dietz, R-Edgewood, voiced concerns.

Clean Slate acts have passed in 12 other states. Moser plans to propose the legislation in the 2024 legislative session, which starts in January.

She proposed such legislation in this year’s session, but it wasn’t assigned to a committee. Moser’s bill would expunge convictions for nonviolent crimes if five years had passed since an incarceration or non-monetary conditions of release and if the individual had not been convicted of a felony or misdemeanor in the previous five years.

Under Moser’s bill, the Administrative Office of the Courts would send a list of convictions eligible for expungement to the local court that issued the conviction. Within 30 days, the court would order the eligible charges vacated and records, including law enforcement records, expunged.

The court also would notify the person whose record had been expunged. (Moser’s 2023 bill gave the AOC a couple of years to prepare for the change.)

“I think that maybe we should let individuals serve out their sentence and get on with their life,” Moser said. “That is the point of corrections.”

The representative indicated that lawmakers have often talked about “the difficulties that individuals have when they have a criminal record and … the things that they face when they’re seeking employment, education and training or even housing.”

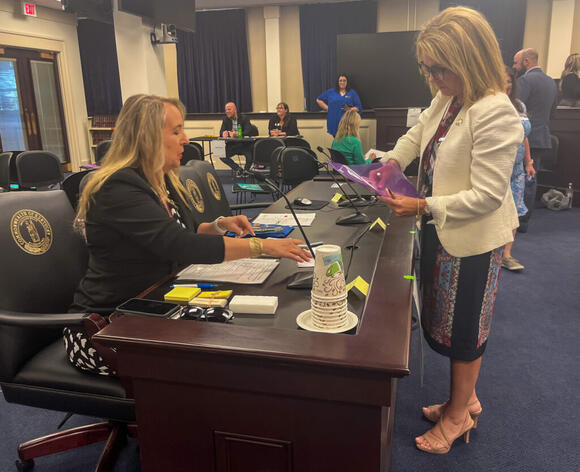

Rep. Stephanie Dietz, R-Edgewood, right, takes part in a “reentry” simulation led by Goodwill Industries of Kentucky. (Kentucky Lantern photo by McKenna Horsley)

In fact, before the committee meeting, a couple dozen state lawmakers took part in an hour-long “reentry simulation,” in which participants demonstrated challenges formerly incarcerated individuals face when rejoining society. Goodwill Industries of Kentucky, one of the organizations supporting an automatic expungement law, led the program.

John Schickel (LRC Public Information)

In 2019, the legislature broadened Kentucky’s expungement laws by making most Class D felonies , the least serious felony offenses, eligible for expungement. Those seeking to expunge a Class D felony must complete a certification process, petition a court and pay a $300 fee. Moser said fewer than 10% of people eligible for expungement petition the court.

Schickel didn’t support the original expungement bill and declared that he still doesn’t during the meeting. He asserted small businesses or others conducting a background check should have all the information they can. Based on his experience at past reentry fairs, Schickel said businesses are “just begging to hire people with records,” but not enough people apply.

“Who are we to say that small businesses, or a little old lady, or somebody that’s hiring somebody, or someone that wants to do a background check on somebody they’re bringing into their business — who are we to say that the government can hide that from us?” Schickel said. “I don’t understand that.”

Moser disagreed. Before taking up the bill, she thought businesses have a right to that information but after further exploring the topic, believed a closer look should be taken on punishment from the courts.

Dietz told presenters that she had heard from officials such as commonwealth’s attorneys that the proposal conflicts with Marsy’s Law , a 2020 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution that requires the victims of crimes to receive notices about their case and those accused, as well as concerns about not paying restitution before granting an expungement.

Jesse Kelly, a campaign strategist for the Clean Slate Initiative , responded that completing a sentence now requires an individual to pay all fines and restitution. Individuals who have not met all of their sentencing requirements would not be eligible for exoneration.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics says 19,580 people are released from Kentucky prisons each year.

Kentucky incarcerates its residents at a higher rate than the nation as a whole. In Kentucky, the rate of prisoners under the jurisdiction of state correctional authorities in 2020 was 414 per 100,000 residents compared with the national rate of 359 per 100,000, according to the National Institute of Corrections.

Kentucky’s workforce participation rate — 57.8% seasonally adjusted in June — is in the bottom 10 states.

The post A ‘clean slate’ for Kentuckians convicted of nonviolent or low-level crimes? appeared first on Kentucky Lantern .

![Foothills-Bundle] Foothills-Bundle](https://thelevisalazer.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Foothills-Bundle-422x74.jpg)