|

| Manchin and then-VP Biden in 2017 (Photo by Tom Williams, Roll Call) |

West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s pivotal position in the federal government – “He can shoot down filibuster reform, shape the economic recovery or moderate liberal hopes for the minimum wage” – makes Democrats “laugh uneasily” and say “So just give the man what he wants,” writes Emily Badger of The New York Times. “But there is a deeper possibility in this unusual alignment of one senator, one struggling state and one suddenly attentive capital.” And it could make a difference in more than West Virginia.

“West Virginia and Appalachia deserve an outsized piece of any federal recovery policy,” Kelly Allen, executive director of the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, told Badger, who writes, “That’s because the region’s decades-long role in powering the nation through coal, she said, came at enormous cost to the health of local residents, their environment and their economy. A serious federal response to that history could both bolster the state and be a model for other parts of the country that have been left behind.”

Appalachian liberals like Allen “dream of broadband, vast brownfield cleanup efforts, greater aid to community lenders who operate where traditional banks won’t, more resources for high-quality housing and health clinics — investment on a scale that would return to the region all the wealth that was taken out of it by resource extraction,” Badger writes. That happened mainly in West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky, which is represented by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and a conservative but relatively spending-friendly Republican, Rep. Harold “Hal” Rogers of Somerset, member and former chair of the House Appropriations Committee.

Appalachia has lessons for the rest of the nation. It was one of the first rural regions that have fallen further behind “as other places grow more prosperous,” as “globalization and knowledge work began to reorder the economy, with tremendously unequal consequences depending on where you live,” Badger writes. “Today, however, no one in Washington is responsible for confronting that pattern, said John Lettieri, the president of the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington think tank that has proposed a new cabinet-level office to do that.” Members of Congress and others have made similar proposals, and the Biden administration appears to be listening.

Badger offers examples of why high-level coordination is needed: “Some health programs devote extra resources to rural communities, but misclassify which ones are “rural.” The federal government incentivizes banks to invest in struggling neighborhoods. But those incentives don’t work well in rural communities with no local bank branches. The government also has an array of tax credit programs to support development. But they work best with large-scale urban projects, not small rural ones.”

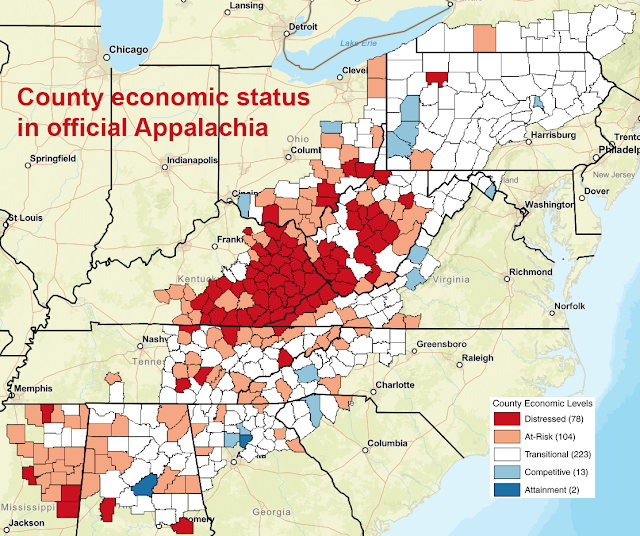

This map from the Appalachian Regional Commission, adapted by The Rural Blog, shows Eastern Kentucky is the heart of economic distress in Appalachia. To enlarge, click on it.

![Foothills-Bundle] Foothills-Bundle](https://thelevisalazer.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Foothills-Bundle-422x74.jpg)